Paper Money Began as Receipts for Gold and Silver held in vaults

It's good to remember fundamentals and watch for the warning signs where today's deviation from the basics will wipe out "companies" like "Bank of America"

Silver News First

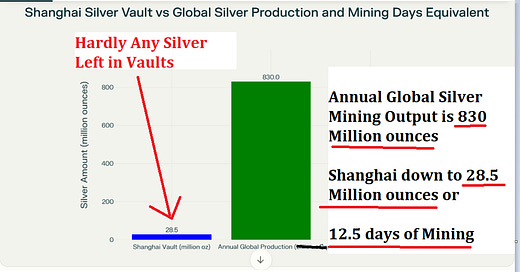

SGE Silver Vaults Down

Shanghai Silver vaults hit the lowest level in 11-month

down 47 Tons this week to 887 Tons or 28.5 m ounces

Global silver mine production is approximately 830 million ounces annually.

To replenish 28.5 million ounces (Shanghai’s vault decline):

Daily production: ~2.27 million ounces (830M ÷ 365 days)

Days required: ~12.5 days (28.5M ÷ 2.27M/day)

end of segment

Gold and silver have been used as money for thousands of years, valued for their scarcity and durability. Historically, paper money began as receipts for gold and silver held in vaults, representing real, tangible wealth stored safely for the bearer.

Look how far we have deviated from this simple concept.

Bank of America’s massive unrealized bond losses-estimated at $111–$112 billion as of early 2025-pose a severe risk to its stability, representing 57% of its tangible common equity. These losses stem from pandemic-era investments in low-yield bonds (1–2%) that plummeted in value as interest rates surged to 4.89% on 10-year Treasuries. With the U.S. Treasury needing to refinance $9.2 trillion in debt in 2025 and issue $28 trillion over four years, rising yields could further erode bond prices, amplifying losses across the banking sector.

The FDIC estimates $500 billion in unrealized losses industrywide, with Bank of America accounting for roughly 20% of this total. While the bank claims its balance sheet remains strong, its strategy of holding depreciated bonds mirrors Silicon Valley Bank’s 2023 collapse, where similar interest-rate risks triggered insolvency. If yields climb to 7–10%, as some fear, Bank of America’s equity could be wiped out, potentially sparking liquidity concerns or depositor panic.

Compounding these risks, the Federal Reserve’s limited control over long-term yields and the Treasury’s reliance on volatile debt markets create a precarious feedback loop. Failed auctions or forced Fed intervention (e.g., quantitative easing) might ignite inflation, further destabilizing the financial system. While a 1932-style collapse isn’t certain, the convergence of soaring refinancing needs, banking-sector fragility, and evaporating investor confidence underscores a systemic vulnerability with few painless exits

Gold and Silver: The Only True Money? Unmasking the Centuries-Old Confidence Game

“Gold is money. Everything else is credit.” The words of J.P. Morgan, uttered in the early 20th century, echo like a warning shot through the centuries. But how did we arrive at a world where this truth is not just ignored, but actively inverted-where money is conjured from promises, and the bedrock of civilization is replaced by shifting sands of credit and confidence? To answer that, we must follow the bucket brigade of history, passing the torch from temple vaults to Venetian bankers, from Medici ledgers to the shadowy halls of the Federal Reserve.

Was there ever a time when money was truly money-tangible, immutable, and universally trusted? In the ancient markets of Mesopotamia and Egypt, gold and silver were not just symbols of wealth, but the very substance of commerce. Their durability, scarcity, and universal appeal made them ideal stores of value, and the first standardized coins-struck in Lydia, Persia, and Rome-became the arteries through which the lifeblood of trade flowed.

But as kingdoms grew and wars multiplied, a new breed of financier emerged. What happens when the guardians of gold become its gatekeepers? In medieval Venice, the state, desperate to fund its endless wars, locked away citizens’ gold and silver and issued “prestiti”-state bonds-turning private wealth into public debt. Spain called its war bonds “juros,” France “rentes,” and soon, the entire continent was addicted to the alchemy of paper promises backed by vaults of precious metal. But what was really in those vaults, and who controlled the keys?

Did the villagers know that their crisp notes were just claims on a treasure they would never see? For centuries, paper money was little more than a receipt-a draft or bill, a promise to pay in “real” money, meaning gold or silver. But as the paper multiplied, the metal backing it thinned. In France, John Law’s Banque Royale issued so many notes that the first great paper money inflation ended in ruin, a lesson quickly forgotten as assignats and later francs flooded the land.

Who benefits when the promise becomes the product? The Medici of Florence, the Rothschilds of Frankfurt, the Bank of England’s founders-each new generation of bankers refined the art of control. In 1694, when King William III needed funds to fight France, forty businessmen pooled their resources to create the Bank of England, with the explicit right to issue currency and, more importantly, to control it6. The king got his navy, the bankers got the kingdom’s purse strings.

At what point does money lose its anchor to reality? The 19th century saw the rise of central banks and the gradual replacement of silver and gold with banknotes and token coinage, their value “guaranteed” by reserves held in secretive vaults. But the final break came with the advent of fractional reserve banking, a system where only a small fraction of deposits are actually backed by anything tangible. The rest? Pure credit-faith, hope, and, as history shows, eventual betrayal.

Why did the world’s greatest democracy hand its money supply to a private cartel in 1913? The Federal Reserve Act, signed by Woodrow Wilson, was sold as a cure for banking panics. But as Wilson himself later lamented, “A great industrial nation is controlled by its system of credit… a Government by the opinion and duress of a small group of dominant men”. The Fed, a quasi-public, quasi-private institution, now creates money “out of thin air,” buying government bonds, setting interest rates, and expanding the money supply at will. The villagers’ gold is long gone; in its place, a web of debt and promises, managed by unelected technocrats.

Does anyone remember that the temple of Solomon was once the world’s central bank-its vaults the repository of both spiritual and material wealth? Today, the temples are glass towers, the priests wear pinstripes, and the rituals are conducted in the language of derivatives and quantitative easing. The global financial system, like the temple before it, is built on confidence, perception, and carefully managed narratives. But what happens when the story unravels?

Will the next crisis remind us that only gold and silver are money, and everything else is credit? Or will we double down on the illusion, trusting that the hand that gives is still above the hand that takes? The answer, as history suggests, depends on how long the villagers are willing to believe that the emperor’s notes are worth more than the gold and silver they once represented.