Coin clipping, a sneaky and significant form of monetary fraud, involved the meticulous shaving or cutting of small amounts of precious metal, typically gold or silver, from the edges of coins.

This crime, deeply rooted in history, was a prevalent issue in the 17th and 18th centuries, a time when coins were hand-struck and contained metal equal to their face value.

Even pirates (Yes, those spirited and swashbuckling thieves) considered gold clippers the worst criminals. (the lowest on the pecking order of thieves)

Pirates considered themselves brave, with some street cred and living legends acting out blatantly and brazenly, whereas the gold clipper was considered a sneaky coward.

Fascinating insight these Pirates had.

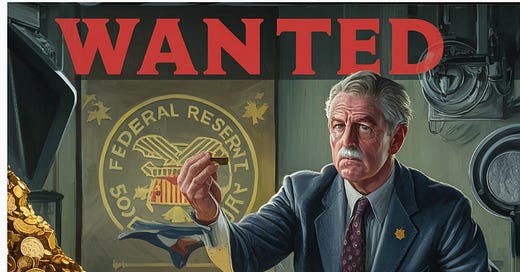

Later, we will be drawing intriguing comparisons between the gold clippers and modern financial figures like Jamie Dimon or Jerome Powell.

In 1823, Oliver Taylor went from being a hero to being a no-name zero (literally, his headstone was left blank; he was sentenced to death by hanging.)

Oliver Taylor was caught and killed for being a Coin Clipper.

Today, we can draw parallels between the historical practice of coin clipping and modern financial schemes. The complex interactions between the Federal Reserve, US Department of Treasury, Paper Derivative Gold and Silver Trades, and

CRIMEXComex Futures can be seen as contemporary versions of the convoluted gold clipper scams.

Coin clipping, a nefarious practice prevalent in the 17th and 18th centuries, involved surreptitiously shaving or cutting precious metal from the edges of gold or silver coins.

These coins, hand-struck and intrinsically valued by their metal content, were prime targets for unscrupulous individuals like Oliver Taylor, a notorious coin clipper from Manchester, England.

Taylor, and others of his ilk, employed various methods to execute their scheme. Coins were often "sweated" – shaken vigorously in a bag to dislodge metal particles – or meticulously filed and sheared. The accumulated clippings were then melted into bullion, a form of pure metal easily sold or repurposed into counterfeit coins. These clipped coins, subtly diminished in weight but bearing the same face value, seamlessly entered circulation, enriching the clipper at the expense of the unsuspecting public.

Beyond the direct profit from selling the bullion, Taylor and his contemporaries could exponentially increase their gains by minting counterfeit coins from the stolen metal. This practice exacerbated the economic turmoil caused by coin clipping, as the circulating currency became increasingly unreliable and difficult to value accurately.

The insidious nature of coin clipping eroded trust in the monetary system, hindered trade, and sparked economic instability. To thwart these criminal endeavors, coins were eventually designed with distinctive ridges, making clipping far more evident. Furthermore, severe penalties, including the ultimate punishment, were instituted to deter potential coin clippers like Oliver Taylor.

How the Crime Worked

Clipping Process: Clippers used tools like shears or files to remove metal from the edges of genuine coins. This was sometimes done by "sweating" coins, which involved shaking them in a bag to collect metal dust.

Melting and Selling: The collected clippings were melted down into bullion, which could be sold or used to make counterfeit coins.

Circulation of Clipped Coins: As long as the clippings were not too excessive, the diminished coins could still circulate as if they contained their full metal value. This allowed clippers to profit from both the clippings and the continued use of the original coins

Throughout history, there have been hundreds of instances where traders or governments manipulated the prices of commodities like gold, silver, and oil. Here are some notable examples across different eras:

Ancient Rome

Currency Debasement: During the Roman Empire, particularly under emperors like Nero and Caracalla, there was significant debasement of currency. The silver content in the denarius, a major Roman coin, was gradually reduced, leading to inflation and economic instability. By the time of Gallienus, the denarius contained only about 5% silver, which caused prices to skyrocket across the empire. This manipulation of coinage to create more money while reducing its intrinsic value is a historical example of economic manipulation.

European Examples

Dutch and English Manipulations: In the 17th century, the Dutch and English were involved in manipulating the prices of commodities through their trading companies. The Dutch East India Company and the British East India Company had significant control over the trade of spices, tea, and other valuable commodities, effectively controlling prices through monopolistic practices.

Modern Day Examples

London Gold Fixing: In the modern era, there have been instances of manipulation in the gold market. The London Gold Fixing, a twice-daily conference call among five bullion trading firms, was accused of manipulating gold prices for over a decade. This manipulation involved setting the price of gold to benefit traders at the expense of clients.

Libor Scandal: Although not directly related to gold, the Libor scandal involved the manipulation of interest rates by major banks, which had wide-reaching effects on various financial markets, including commodities like oil and precious metals.

CRIMEXComex

These examples illustrate the long history of price manipulation in commodities, driven by both governmental policies and private trading interests.

But No Price Rigging Scandal is as Big Egregious as what we see today in our Silver Market.

The Comex and LBMA (London Bullion Market Association) markets primarily operate through paper contracts or paper representations of silver and gold. In these markets, the trading is largely based on futures contracts, which are agreements to buy or sell a certain amount of metal at a future date.

These contracts allow investors to gain exposure to the metals without physically holding them. For instance, at Comex, there are often up to 350 to 400 paper claims for each physical ounce of silver available for delivery, indicating a significant leverage of paper contracts over actual metal reserves.

This means that if a small percentage of these contracts (each contract is 5,000 ounces) were to demand physical delivery, the Comex would not have enough silver to meet the demand.

Similarly, the LBMA also deals with a large volume of paper contracts relative to physical holdings.

In contrast, the Shanghai Gold Exchange requires that metal be deposited before trading, ensuring that transactions are backed by physical metal. This approach emphasizes the physical aspect of trading, as opposed to the speculative nature of paper contracts seen in Western markets like Comex and LBMA

Just two days ago…

The

CRIMEXComex had 102 Silver deliveriesThe LBMA had 350.

The LBMA is having a massive delivery year and most of that metal is going to India and China (for solar panels, military, EVs and aerospace)

Also remember that India has recently slashed their import tax (from 15% to 6%)

Plus India and many other countries

obfuscateconceal their military use of Silver (example for torpedoes) by marking their imports as “jewelry” as we reported in the case of Rajesh ExportsYou are witnessing the #silversqueeze

I get dozens of emails daily where people are worried about the fake spot price and we urge them to buy more and then they show us their orders on our Reddit pages

Legal Definition of Force Majeure

Force majeure is a contractual clause that relieves parties from their obligations when an unforeseeable and unavoidable event, beyond their control, prevents them from fulfilling their contractual duties. These events can include natural disasters, war, or other significant disruptions. The clause is designed to allocate risk for such events, and its applicability depends on the specific language within the contract and the jurisdiction's legal standards.

Force Majeure in Commodity Markets

In the context of commodity markets like the COMEX, where traders often deal in paper derivatives rather than the physical commodity, force majeure can be invoked if unforeseen events disrupt the delivery or settlement of contracts. This is particularly relevant when traders who have short positions (obligated to deliver the commodity) face difficulties in fulfilling these obligations due to external disruptions.

Paper Derivatives and Physical Delivery

On exchanges like the COMEX, many traders engage in futures contracts that are settled in cash rather than through physical delivery of the commodity, such as silver. This practice can lead to a situation where the actual physical supply of the commodity is less than the volume of paper contracts. If a large number of traders suddenly demand physical delivery, it can lead to a shortage, causing those with short positions to struggle to meet their obligations, potentially leading to a force majeure declaration.

Recent Example: Nickel Market

A recent example of such a scenario occurred in the nickel market. In March 2022, the London Metal Exchange (LME) suspended nickel trading after prices surged dramatically due to a short squeeze. A short squeeze occurs when traders who have bet against a commodity are forced to buy it at higher prices to cover their positions. This led to a liquidity crisis and significant disruptions, prompting discussions around force majeure as traders were unable to meet margin calls or deliver the physical nickel.

Potential for Force Majeure in Silver Market

In the silver market, similar dynamics could unfold if a large number of traders demand physical delivery simultaneously, especially if the available physical silver is insufficient to meet these demands. This could lead to a situation where traders cannot cover their short positions, potentially invoking force majeure clauses to excuse non-performance due to the unforeseen shortage.

In summary, force majeure in the context of the silver trade on COMEX could be triggered by a significant mismatch between paper contracts and physical silver availability, leading to a situation where traders cannot fulfill their delivery obligations due to unforeseen market disruptions.

end of section

New Shanghai Data: Silver Vaults Vanishing. Silver Drained by 2025 (at this rate)

Pericles is considered the most influential Athenian leader during the Peloponnesian War. As a skilled statesman and general (strategos), he shaped Athens' strategy for the conflict.