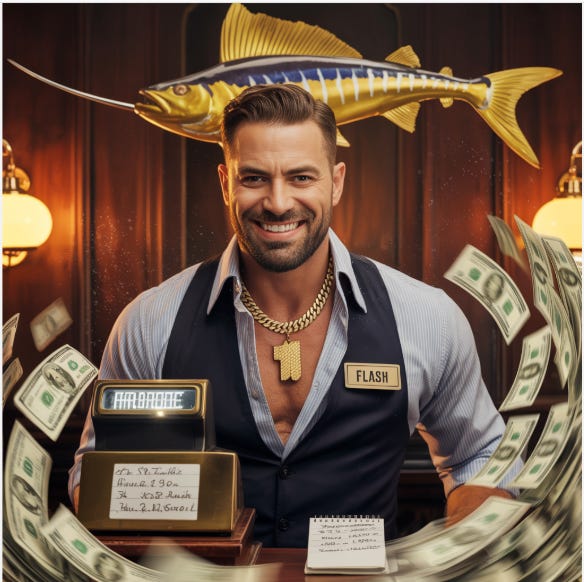

And in a FLASH...The Money Disappears.

A Bartender’s Trick, a Government Trend: How Skimming—from Bar to Beltway—Lines Pockets and Drains Public Coffers

Skimming: From the Bar to the Beltway

Picture this: a bustling surf and turf restaurant, alive with the clatter of cutlery and the hum of conversation. At the center of it all is Flash, the bartender, who’s figured out a way to make his own version of “happy hour” last all night.

On a busy night, the bar rings up over $5,000 in sales. Draft beers go for $7, glasses of wine for $10, and cocktails for $15. Enter Flash’s sticky note system: a tiny piece of paper with cryptic marks—1 for beer, 2 for wine, 3 for cocktail. He charges customers, puts the cash in the drawer, but never officially rings up the sale. Flash does ring up the majority of drinks but every tenth drink or so he doesn’t (so 10% of the time) - This means he makes $500 extra per shift.

At the end of the night, he tallies the marks, pockets the cash, and—like magic—the money is gone in a flash. Classic skimming.

Skimming, in plain terms, is pocketing cash before it ever gets officially recorded. It’s a favorite trick in restaurants, bars, and retail, but it’s far from unique to the private sector. In fact, the art of skimming has made its way into the halls of government and the sprawling supply chains of the defense industry—just on a much grander, and more expensive, scale.

Let’s follow the supply chain. When the U.S. reports its defense budget, it’s not just the Department of Defense. The Department of Energy, for example, also plays a key role in national security. But the real story isn’t just about what’s budgeted—it’s about what actually gets spent, and how. You’ve probably heard about the $700 hammer, or the $500 toilet seat, or the $900 trash can. These stories may be anecdotal or exaggerations—but they point to a real problem: a labyrinth of bureaucracies that often overlap, duplicate, or even contradict each other, making it easy for money to slip through the cracks.

Consider how a company like TransDigm can overcharge the Pentagon by as much as 3,800% on routine parts, simply because the rules prevent contract officers from knowing the actual cost of items.

The Pentagon Inspector General found more than 100 overcharges by TransDigm alone, totaling $20.8 million. Multiply that across the entire defense supply chain, and you’re talking about billions of dollars lost to waste, fraud, and abuse.

Skimming in government takes many forms. Contractors might pad invoices with unnecessary costs, bill for work not performed, or provide substandard goods and services. Sometimes, companies collude to rig bids, ensuring a pre-determined winner gets the contract. Other times, they misrepresent their qualifications or inflate hours worked. These tactics are all ways of skimming money from the public purse, just like Flash skims from the bar’s till.

The consequences are serious. Under the False Claims Act, companies caught defrauding the government can be forced to pay back three times the amount stolen, plus penalties for every false claim. They can also be barred from future contracts, face criminal charges, and even jail time.

But the real losers are the taxpayers, who foot the bill for this waste.

So, what’s the takeaway? Skimming isn’t just a bartender’s trick—it’s a systemic issue that affects everything from your local bar to the Pentagon. Whether it’s Flash’s sticky notes or a defense contractor’s padded invoice, the principle is the same: money is diverted before it’s officially accounted for. The difference is scale. Flash might pocket a few hundred dollars on a busy night. In government, the stakes are much higher—billions of dollars, and the trust of the public, are on the line.

By understanding how skimming works—from the bar to the Beltway—we can better spot the signs, ask tougher questions, and demand greater accountability. After all, whether it’s Flash or a defense contractor, no one likes to see their hard-earned money disappear in a flash.

Distortions in the GDP

Now, let’s talk about the absurdity of GDP—the Gross Domestic Product. When the Joint Chiefs of Staff decide to spend 20 years in Afghanistan, only to abandon tens of thousands of Humvees, nearly a hundred Blackhawk helicopters, and countless tanks and rifles, the entire $2.3 trillion spent gets tallied up in the nation’s GDP. Here’s the kicker: whether those resources are used wisely or left to gather dust—or even destroyed—doesn’t matter to the GDP calculation.

Government spending is government spending, full stop. It’s as if a general ordered his troops to dig 10,000 holes in the desert one week, then told them to fill those same holes back in the next. Both the digging and the filling would boost the GDP, even though nothing of lasting value was created. This quirk in economic measurement means that the GDP can grow simply because money is being spent, regardless of whether the spending is productive, wasteful, or downright nonsensical. It’s a sobering reminder that, while GDP may tell us how much we’re spending, it doesn’t always tell us how well we’re spending it.